Experts of the Dresden State Art Collections were astonished when they closely examined Vermeer’s “Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window” using technical equipment: Under a layer of paint hid a youthful Cupid.

The artist had painted the figure on the wall behind the girl, who seems to be reading innocently. After two years of work to reveal the original, the painting was presented to a surprised audience.

Alongside Rembrandt and Rubens, Dutch painter Jan Vermeer (1632-1675) is considered one of the most famous artists of the Baroque period. His “Girl Reading a Letter” was and is considered one of the best works of the Dutch Golden Age between 1600 and 1700, during which the Netherlands prospered politically, commercially and culturally.

With only 37 paintings, Vermeer’s oeuvre is rather small, contributing to the excitement that the finding in Dresden triggered in the world.

The museum is now celebrating the painter with the exhibition “Johannes Vermeer. On Reflection.”

-

From Rembrandt to Picasso: Artworks that were painted over

Rembrandt’s legendary ‘Night Watch’

Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum closely examined Rembrandt’s most famous painting over the past two years, using state-of-the-art technology. It turned out that Rembrandt first made a sketch on the canvas, painted over it and made several changes as he was going along. “We have discovered the genesis of ‘The Night Watch,'” director Taco Dibbits said, calling it a “breakthrough.”

-

From Rembrandt to Picasso: Artworks that were painted over

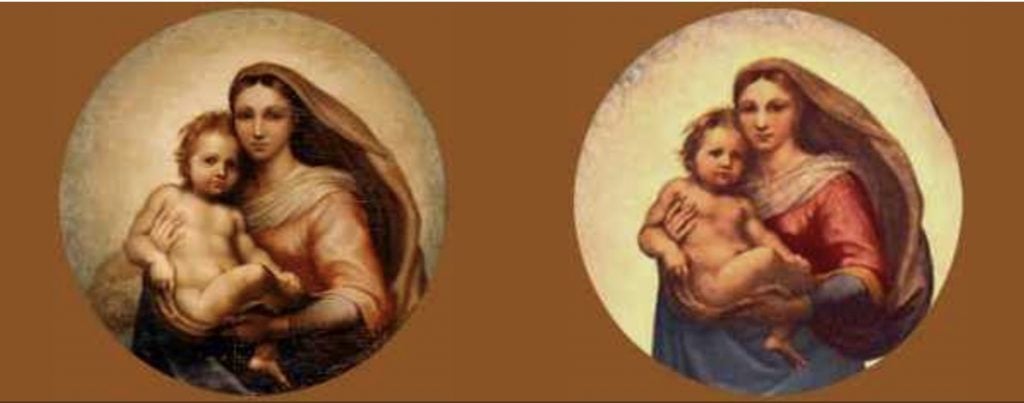

Vermeer and a canceled-out cupid

People are familiar with Johannes Vermeer’s “Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window” (ca. 1657-1659) in its version on the left. Two years ago, researchers discovered a naked cupid figure that had been painted over. The painting, cupid and all, is on display in the Dresden exhibition “Johannes Vermeer. On Reflection” in its original state until January 2, 2022.

-

From Rembrandt to Picasso: Artworks that were painted over

Jan van Eyck’s mystic lamb

Last year, people were surprised at a discovery in the Ghent altarpiece made during restoration work. The Flemish painter Jan van Eyck (about 1390 to 1441) had not painted the lamb as shown on the left, but actually as seen on the right, with a narrow snout and a piercing, downright human-like gaze. The uncovered original was mocked in social media.

-

From Rembrandt to Picasso: Artworks that were painted over

Cover them up in Michelangelo’s ‘Last Judgement’

The version we see of Michelangelo’s “Last Judgement” (1534-1541) in the Sistine Chapel does not correspond to the original. The figures he painted around Jesus Christ were stark naked. His contemporaries felt that was obscene, so they commissioned his student Daniele da Volterra to add pants to the nude figures. He went down in history as “braghettone” (the breeches painter).

-

From Rembrandt to Picasso: Artworks that were painted over

Van Gogh’s wrestlers painted out with flowers

Vincent van Gogh painted over many of his pictures. Money was too tight to keep buying new canvases. In 1886, he painted “Still Life with Meadow Flowers and Roses” over two half-naked wrestlers he had created at the Antwerp Art Academy (right). It wasn’t until 2012 that the flower painting was clearly attributed to van Gogh.

-

From Rembrandt to Picasso: Artworks that were painted over

Female portrait, ravine and lush vegetation

More painted-over works by van Gogh: the painting “Wild Vegetation” (bottom left) was discovered under “Ravine” (top left). The two paintings were created four months apart. In 2008 researchers used special X-ray technology to find a portrait of a woman under his painting “Grasgrond” (right). They were able to reconstruct the dark portrait in great detail.

-

From Rembrandt to Picasso: Artworks that were painted over

Picasso: Stick to the lines

Thrifty, Pablo Picasso once used a canvas for “La Misereuse accroupie” (1902) that had already been painted on by an unknown artist. In 2018, a Canadian research team discovered a landscape and a hand underneath the woman with the blanket. Picasso even used the existing lines for his painting.

-

From Rembrandt to Picasso: Artworks that were painted over

Max Pechstein: Hide what you don’t like

For almost a century, Max Pechstein’s “Lady with Hat” (1910) was hidden behind a flower still life. Pechstein probably canceled out the original with its bright colors because he wasn’t happy with it. He preferred to hide what nowadays is seen as Expressionism and considered worthy of protection.

-

From Rembrandt to Picasso: Artworks that were painted over

Giacometti: Self-doubt about his work

Swiss painter and sculptor Alberto Giacometti (1901-1966) painted over his pictures again and again, not only out of lack of money but because he was dissatisfied with his work. When he painted, he cursed, lamented, and started over again. It took him 18 days to paint the portrait of his friend James Lord.

-

From Rembrandt to Picasso: Artworks that were painted over

Georg Baselitz: An invisible painting

“I dream of painting an invisible picture,” Georg Baselitz said in 2013. But how? By making it disappear under layers of black paint. “Joseph Beuys simply placed the painting with its back to the viewer, preserving the mystery. That’s roughly how I imagine it,” he said — an entirely different approach from that of his colleagues over the centuries.

Author: Bettina Baumann

“Uncovering parts of paintings that have been drawn over is not always as meaningful as in the case of Vermeer,” says Maria Galen, expert for modern art and gallery owner in the western German city of Greven.

“Vermeer used the figure of cupid four times — as a ‘picture-in-picture,'” according to Uta Neidhardt, senior art conservator at the Dresden Museum.

Research and state-of-the-art laboratory tests have unambiguously confirmed that the love god, painted in brown and ochre tones, was covered up by a different hand that also covered up the amorous statement Vermeer originally wanted to make. But the case is not always this clear.

Searching for the perfect picture

What complicates the matter is the fact that pictures can be painted over in the most varied of ways.

Cologne’s Wallraf-Richartz Museum is currently holding an exhibition called “Revealed! Painting techniques from Martini to Monet.” A section of the exhibition engages with such artistic interventions.

“Painters have always sought the perfect picture,” says Iris Schaefer, chief art restorer at the museum. “There are only a few paintings, which are free of pentimenti,” she adds.

“Pentimenti,” the singular form of which is “pentimento,” essentially means the presence of images that have been painted over. This includes corrections, changes in motif and color, and even artistic interventions to the point of complete destruction of artworks.

An X-ray of Renoir’s ‘A Couple’ revealed a completely different picture

But what drives artists to change their work? “There were many reasons for that,” Schaefer says. Sometimes artists had doubts regarding their self-worth, often actual life crises. Then again, criticism from observers, art dealers or buyers had consequences for the artwork.

But were “pentimenti,” or later changes in a painting by someone else, also executed to adjust the artwork to new moral ideals? According to Schaefer, it is not always easy to differentiate between the two.

In order to reveal the secrets of old paintings, restorers today use a growing arsenal of investigative methods. Even observing with the naked eye can reveal brush strokes which point to possible overpainting. Stereo microscopes allow 3D-vision with up to 90 times magnification. X-rays, infrared and ultraviolet rays seep into different depths of the picture’s surface and convey painting canvases or signature lines.

Art technologists at the Wallraf-Richartz Museum were astonished when they X-rayed “A Couple” by August Renoir (1841-1919).

Instead of the man and woman standing together at a park seen on the 1868 oil-on-canvas painting, the X-ray revealed a completely different image of two women sitting opposite to each other. “We thought we had pulled out the wrong painting from the developer fluid,” Schaefer remembers.

Art restorers are now analyzing Rembrandt’s ‘The Blinding of Samson’

The chemistry of color

Even more astonishing is the macro X-ray fluorescence analysis, or MA-XRF, which is a sophisticated method that allows the observer to look under the surface of an object without causing any damage.

The process helps recognize the composition of colors and comprehend the painting process. As part of a big research project, the Frankfurt Städel Museum has already exposed unknown parts of the Altenberger altarpiece using a process called “Element mapping.”

-

Friends and family: Rembrandt’s social network

Portrait of Rembrandt by Jan Lievens (1629)

An old friend of Rembrandt’s, Lievens captured the painter known for his impressive self-portraiture. The two artists, friends since childhood, shared a studio in Amsterdam until 1631, when Lievens began to travel for his career. Rembrandt, in contrast, never went abroad, although he is said to have been inspired by the Italian masters

-

Friends and family: Rembrandt’s social network

Portrait of Saskia (1652-1654)

A growing middle class made portraiture a dominant style of the era, as their wealth and desire to be documented led to the commissions that supported artists. Rembrandt often used his brush to capture the likeness of family members, including his wife Saskia Uylenburgh. Her family made up a large part of his social and financial life.

-

Friends and family: Rembrandt’s social network

Portrait of Arnold Tholinx (1656)

With marketing done mainly via word of mouth, Rembrandt had to rely on friends and collectors to drum up interest in his talent. It must have been his friend, the collector Jan Six, who led to this commission featuring the well-known physician, Arnold Tholinx. Six’s brother-in-law, Tholinx was the focus of other works by Rembrandt, including a sketch that is part of the Rijksmuseum’s collection.

-

Friends and family: Rembrandt’s social network

Light study with Hendrickje Stoffels as model (1659)

Hendrickje Stoffels moved in with the artist after the death of his wife, Saskia. After Rembrandt lost his house due to debts in 1658, his son, Titus, and Hendrickje banded together to sell the artist’s paintings, a move that kept debt collectors at bay. Unable to marry Hendrickje without losing the inheritance Saskia left him, the couple simply lived together until her death in 1663.

-

Friends and family: Rembrandt’s social network

Portrait of Titus (1660)

While his son, Titus, seen here at 19, worked for his father throughout his life. It wasn’t until Rembrandt went bankrupt in 1656 that Titus, together with Hendrickje Stoffels, started a gallery of the artist’s work to pay off creditors. The painting, on loan for the first time for an exhibition in Europe, reflects Rembrandt’s approach to portraying family and friends: informal, personal, relaxed.

Author: Courtney Tenz

Since spring 2021, one of the main paintings in the museum, Rembrandt’s “The Blinding of Samson” is under the scanner.

The master’s works are being researched not only from the point of view of art history, but also using the latest technology, as was the case during the huge research and restoration project called “Operation Night Watch” that was carried out by the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam.

During Rembrandt’s time, the owners of his famous painting “The Night Watch” had cut it with scissors so it could pass between doors. The restoration process allowed experts to reconstruct the missing pieces of the work.

Cologne art restorer Iris Schaefer admires the global museums in Amsterdam, Frankfurt, London and Washington, which have financial resources for devices that cost millions. “Incredible to see all that’s possible,” she says, although artists were not always happy with everything that resulted from technology and the art of restoration.

A change in attitudes

In the past centuries, artists restored their own works and thanks to their skills, they were also hired to maintain and improve other artworks. Even in the 19th century, it was common to overpaint and regild damaged artworks. “I cannot believe that artists were happy with this,” Schaefer says.

An MA-XRF image of ‘The Blinding of Samson’

Only around 1900 did painters begin specializing as restorers and the profession was born.

To become a restorer in Germany today requires a university degree. Art history is mandatory as is an understanding of technology. “Our profession is linked to a code of conduct,” Schaefer says. “There are strict rules regarding intervention in art and cultural objects.” The integrity of the artwork has the highest priority. “There has been a change of attitude here,” she adds.

A change that has also proven beneficial for Vermeer’s “Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window.” For a long time, the painting stood for the meager interior of a chaste soul. The empty wall with the girl’s dainty silhouette emphasized the contemplative stillness of the work.

After 200 years, the painting now tells a completely different story: behind the girl is a naked youth. The window is open, the curtain in front of Cupid is drawn to a side, a bowl of fruit spills over with shiny apples and delicate, fuzzy peaches, possibly displaying the tension between external calm and inner tumult, or even longing for love. Vermeer’s original secret seems to have been revealed.

This article was translated from German.