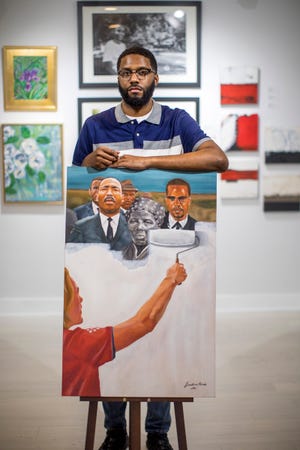

Sylvester Stallone on Why He Painted ‘Rocky’ Before He Wrote the Movie, and Why It Took Him So Long to Come Out as an Artist

Before Sylvester Stallone wrote Rocky and turned the film into an Academy Award-winning classic, he painted its physically tough but internally bruised protagonist. It was the early 1970s and the struggling actor was being repeatedly cast for minor “bad guy” parts, and he felt the urge to illustrate himself as a lead character of contradictions. So he turned to what he knew the best: painting.

“I made a self-portrait with a more defined ‘pug face’ than I had back then, but to capture his sadness, I switched the brush with a screw driver and carved the eyes,” he told Artnet News. That painting, Rocky (1975), is now the crown jewel among the nearly 50 canvases in Stallone’s new survey at the Osthaus Museum in Hagen, Germany.

The exhibition traces the Hollywood leading man’s lesser-known artistic practice through paintings that reflect the hyper-figuration of the 1980s East Village circuit he frequented. He was “a fan of Julian Schnabel’s heavy interaction with the canvas and Keith Haring’s discipline,” he said. The chaotic harmony of Stallone’s celebrated films are often revived in canvas with splashes of bold colors combating amid themes of urban decay and masculine reflection.

The artist never did let go of his first self-portrait, but another “Rocky” painting he made—“my most intense and honest portrait,” he said—now resides in casino magnate Steve Wynn’s collection. And the boxer is not the only cinematic subject in the artist’s repertoire: “I painted the key characters in some of my films, such as Paradise Alley or F.I.S.T.” he said.

Sylvester Stallone, Finding Rocky (1975). Courtesy of Galerie Gmurzynska.

While confident in front of the canvas, Stallone was at first hesitant to publicly exhibit his paintings. Today, an actor or a politician unveiling their artistic side comes as an often unpleasant surprise. Therefore, bringing Stallone’s paintings to daylight about a decade ago required encouragement from his dealer, Galerie Gmurzynska co-owner Mathias Rastorfer.

“He was very discreet and protective of this, but once we saw more works from as long as 50 years ago, it became clear to us,” Rasteorfer said. “If you really immerse yourself in this universe of Stallone’s and don’t deal with it in a prejudiced way, you will realize this has quality.”

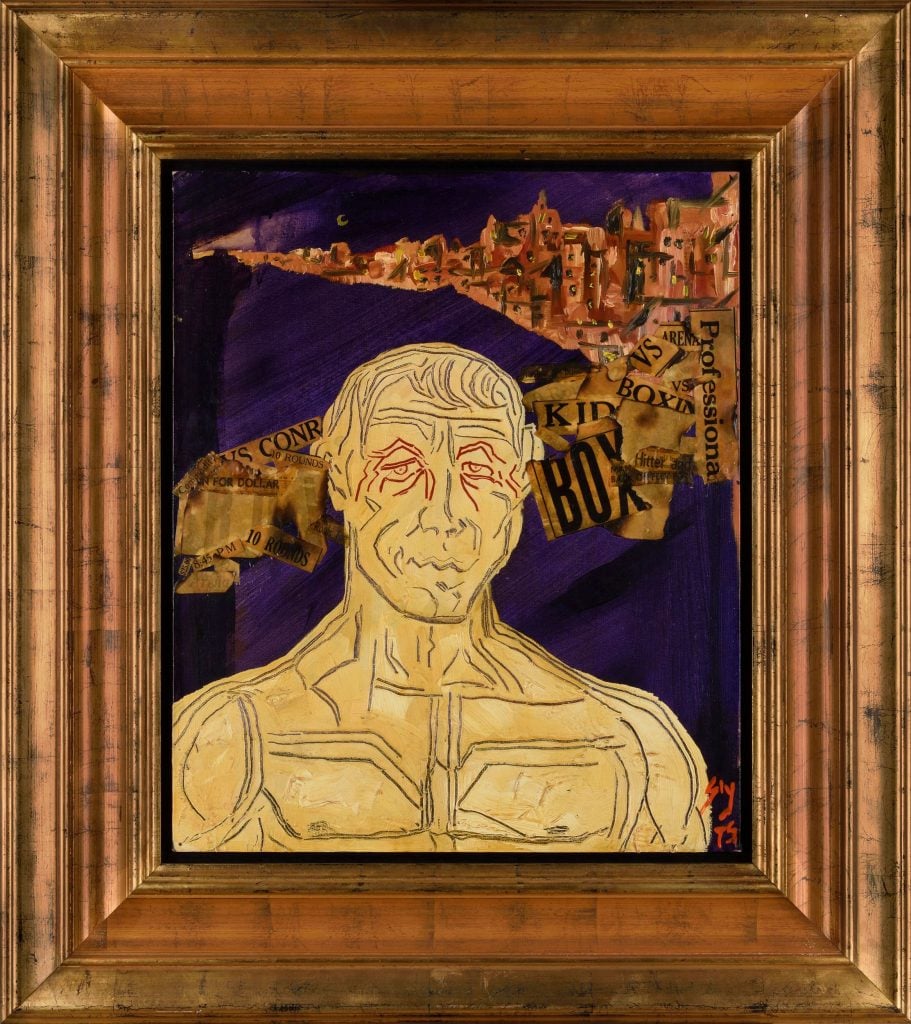

A constant throughout the survey is a rawness of conflicting emotions: despair meets euphoria, or victory pairs with loss. Bright brush marks sweep through hefty bodies rendered with thick lines. The subjects date back to Stallone’s teenage years when he visited museums in New York and Philadelphia, where he was intrigued by the idolized mythological male figures—an inspiration that paved his way into bodybuilding.

“Both in art and film, I looked at figures like Spartacus or Hercules who radiated hyper-reality through their hyper masculinity,” he said. Stallone’s very first drawing, at age 10, depicted an African warrior on cardboard.

Sylvester Stallone, Hercules O’Clock (1991). Courtesy of Galerie Gmurzynska.

Throughout the show, occasional text and sprayed stencils allude to the street culture that gave Sly his first platform as an artist. While studying at the University of Miami, Stallone sold his paintings on dime store-bought cardboards for a few dollars, or the cost of a bus fare up to the northeast.

“My subjects would depend on whatever inspired me, whether it was The Beatles’s ‘Lucy In the Sky With Diamonds’ or an Edgar Allen Poe piece,” he said. “If I crashed a pool party in Miami to sell a painting, I would occasionally be lucky; when I tapped onto someone’s windshield at a gas station in Philadelphia, the answer would usually be simple no.”